In early 1958 the Ministry instructed the Consulting Engineers, Sir Owen Williams and Partners, to investigate possible solutions to this link. The investigation was influenced mainly by three factors:-

1. The traffic pattern which showed that a large proportion of the traffic would originate within the conurbation.

2. The best location for the junction of M5 and M6, and

3. The existing urban development around Birmingham and Coventry, which would determine the amount of demolition on various routs.

While it was clear that peripheral route clear of the built-up areas would reduce the need for demolition, the links to the City and the industrial areas would be long, whereas a more direct route would give better connections to the main centres of activity and population. Careful examination of the possible direct routes showed that, at the expense of more difficult land acquisition and construction, a route through the urban areas was possible without undue demolition, by making use of existing pathways over rivers, canals and existing roads. Such a route was therefore developed and this formed the agreed line for the Midland Links as built.

The project can be conveniently considered in three parts:-

1. A continuation southwards of the M6 from its termination at a point to the south of Stafford, running west of Cannock through Walsall to Ray Hall, a point in West Bromwich, where there would be a free-flowing junction with the M5. (17 miles).

2. A continuation southwards of the M5 from Ray Hall to the termination at Quinton. (11 miles), and

3. A continuation eastwards of the M6 from Ray Hall to the M1 at Catthorpe, passing through the northern edge of Coventry. (38 miles).

The total length of 66 miles consists of 43 miles of rural type motorway and 23 miles of urban motorway, the standards for which were developed along with the planning of the project. The choice of the direct route meant that there was a large structural content and, in fact, there is a total of 13¼ miles of viaduct construction. The section between Gravelly Hill and Castle Bromwich is 3½ miles, which was then the longest continuous viaduct in Great Britain, and was built over the River Tame throughout much of its length, through an industrial area.

Design

The design of the project developed over several years, with the main considerations being the design of the structures and the design of the road junctions, which often had to fit into very limited spaces in the urban areas.

Structures

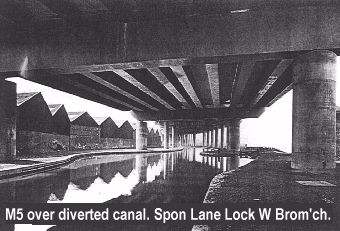

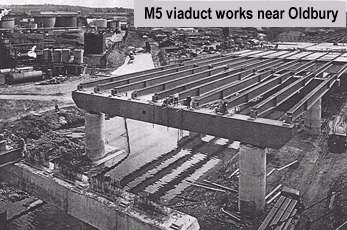

Whereas the rural structures were mostly designed in reinforced concrete, the urban structures, including the main viaducts, had mainly steel deck beams with composite in-situ concrete slabs. In a preliminary design the longest viaduct was intended to be a two tier structure, with the two carriageways one above the other. In the end, however, considerations of joining and leaving the structure, and the problems of flicker from passing the supports of the upper deck, meant that the structure was redesigned in a more conventional single tier form.

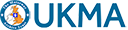

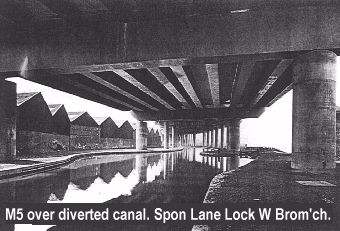

The presence of so many natural and man-made obstructions at ground level meant that many of the viaduct spans were designed individually. Where possible, however, a standard span of 50ft was used with four column supports in concrete, with reinforced concrete in-situ crossbeams. For the standard span the 10 longitudinal beams were standard rolled sections, for the slightly longer spans welded I-section girders were fabricated, either with parallel flanges or, for the longer spans, with varying depth webs. When the use of I-section beams was not possible due to the obstructions at ground level, such as road, river or canal crossings, or the presence of sewage filter beds, fabricated box girders were used. Such box girders were also used for crossbeams when the normal reinforced concrete pattern proved inadequate. The use of fabricated box girders lead to problems at a later stage which are referred to below. Many of the foundations were piled, due to ground conditions and the need to avoid existing hazards such as canals, underground services, etc. and various types of pile were used at different locations.

Junctions

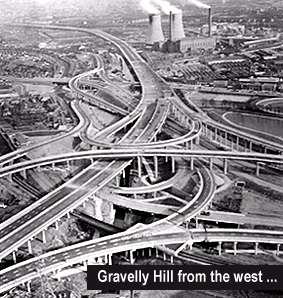

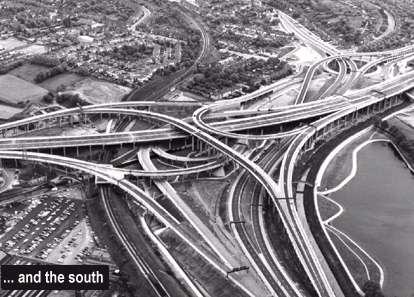

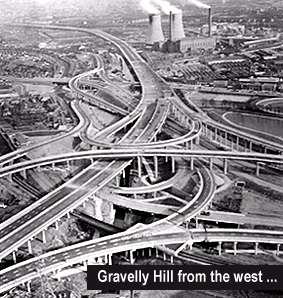

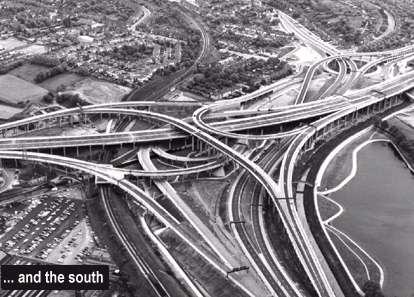

There were 17 junctions on the route, including the terminal junctions linking the project to the M1, M5 and M6. The junction with M1 was a free flow junction with the London direction only on M1. The two most important were the free flow junction at Ray Hall and the multi-level junction at Gravelly Hill where the M6 intersected with the existing very busy junction on the A38 Lichfield Road, and with the Aston Ring Road. This junction, because of the number of intersecting traffic lanes, was inevitably dubbed 'Spaghetti Junction', a name which has stuck and passed into the language. During the design period a re-assessment of the traffic figures showed that too many vehicles were likely to use the motorway for short cut commuting runs, hindering the passage of through traffic, and one junction was removed (Perry Barr) and one made unidirectional (Castle Bromwich).

In the urban areas the incidence of statutory undertakers apparatus meant that a large number of items had to be diverted before and during construction and special steps were taken to plan and co-ordinate this work which cost approximately 5% of the total construction cost. Such items included 440kv overhead electricity lines, 18in diameter high pressure gas mains and a multitude of smaller items. At some junctions it was necessary to produce special sets of multi-coloured plans to ensure that all the services could be fitted into the space available, and in the right order. The majority of the service diversions were carried out by the statutory undertakers on a repayment basis, and this sometimes lead to complex problems of co-ordination and control, as the undertakers had no contractual link with either the consultant or the main contractor.

The Rural Lengths

At either end of the M6 the motorway was normal rural motorway, built to normal standards. Contract 1, at the northern end, had an 11in reinforced concrete carriageway, which had a high cement content, and performed will under traffic. An unusual feature was that the concrete was carried over the bridge decks, being made composite with the deck by 'beehive' bars cast in the deck slab. The other rural lengths all were constructed with a lean concrete lower base, with bituminous base courses and hot rolled asphalt surfacing.

Contract 11, between Coleshill and Corley Service Area, contained the first use of a 'Crawler Lane' to assist traffic flow up a long ascending gradient, a refinement which caused some confusion when first opened as it was unfamiliar to most drivers.

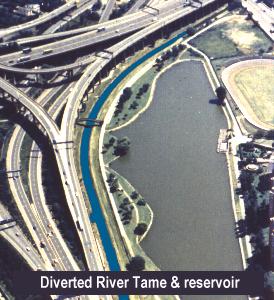

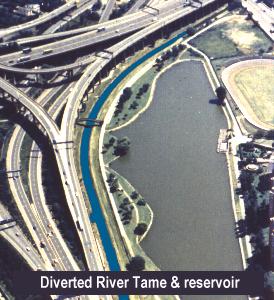

diverted r tame

Construction

The project was split into 16 construction contracts, and unemployed the services of some 13 of the major contractors of the time. Construction was staggered over several years, the first contract starting in September 1963 and the last finishing in November 1971. The total tender price for the 16 contracts was £87.69m. Three of the contracts were carried out in advance of the main motorway construction at those locations. Contracts 3 and 3A involved the construction of railway bridges over live railways in the Walsall area and pre-dated the construction of the adjoining viaduct spans. Contract 8A was very unusual in that it involved the diversion of the River Tame and the consequent reduction in area of a lake adjacent to the Gravelly Hill interchange. The crucial point was that the lake is registered as a Reservoir under the Reservoirs Act, and so the construction of the bund between the river channel and the lake had to be supervised by an Engineer on the register of Dam Engineers.

Supervision of the construction contracts was divided into areas under senior Resident Engineers. Contracts 1 and 2 were carried out individually before the main construction phases started, the other contracts were split into four groups, namely Contracts A, B & C on the M5, Contracts 3, 3A, 5, 6, 7 and 9 on the M6, Contract 8 (the complex Gravelly Hill Interchange) and the rural M6 Contracts 10, 11 and 12. The engineering staff were provided by Sir Owen Williams and Partners, who were assisted by George Corderoy and Company, Chartered Quantity Surveyors, and inspection of the fabrication of steelwork was entrusted to Lloyds Register Industrial Service, with anti-corrosion protection being supervised by R.J.P. Nicklin and Company.

Additional Features

One Service Area was constructed at the same time as the motorway, at Corley to the east of Coventry. The through roads and general infrastructure were constructed by the motorway contractor under a separate contract with the Department of the Environment but the buildings, pedestrian overbridge cladding and fuel services were designed by the architect employed by the developer, Forte. Provision was made, including a pedestrian overbridge, for a further Service Area near Rugby, but this has not been developed at the time of writing.

Five sites for motorway maintenance compounds were provided at intervals along the site, with the facilities being provided by the County Authorities entrusted with maintenance responsibility for that particular length of road. A central maintenance and control office was constructed for the DOE at the Coleshill compound to act as a focal point for the communications system installed in the verges of the motorways.

An experimental anti-dazzle screen, consisting of green plastic 'cricket bats' as mounted on the central reserve safety fence throughout a length of the rural section between Coleshill and Coventry and proved successful, though it did not seem to be generally adopted on other lengths of motorway.

The urban lengths were fully lit, with central reserve mounted columns, and many of the signs and signals were gantry mounted.

Box Girders

During the construction of the viaducts using steel box girders various problems arose with that type of construction on projects quite unrelated to the Midland Links, and using girders of a different scale. However, as a result of these problems, considerable research into the behaviour of box girders was undertaken by others at some speed, and a continuously varying stream of requirements was issued. This involved the strengthening of the girders which were being installed on this project but, due to the speed of the research and the difference between the Midland Links girders and those which were the basis of the research, much abortive work was carried out in welding stiffeners into existing beams, and then amending them to suit the next directive. The main result of these problems was that the opening of the viaduct sections of the scheme was delayed while the amendments were carried out, although the need for much of the stiffening could be questioned.

Post Construction Problems

Various problems arose under traffic during the first few years of use of the viaducts, mainly with the sawn joints in the asphalt surfacing, with the bearings under the rolled steel longitudinal beams, with the road drainage and occasional problems of spalling of the cover to the very heavy reinforcement in some crossbeams.

The original joints in the continuous asphalt surfacing over the standard 50ft spans were sawn joints filled with bitumen. In many locations these joints started to break back from the sawcuts and, due to the difficulty of access under the heavy traffic, no remedial work such as sealing the open edges with bitumen was carried out. This lead to further deterioration and eventually the surfacing had to be cut back or removed and replaced using more modern joint types which had been developed in the meantime.

Due to the large number of beam bearings required and the strong financial pressures on the designers, a simple steel/steel bearing lubricated with molybdenum grease was devised for the standard spans. Unfortunately, over time, these exhibited a tendency to seize up and had to be replaced after some years use by modern proprietary bearings. The longer spans had always had more sophisticated ptfe bearings and continued to perform satisfactorily.

The road drainage system proved difficult to maintain and suffered from damage and neglect and had to be upgraded after some years use.

Conclusions

In spite of being subjected to traffic loads far greater than could have been predicted at the time of design, the Midland Links have performed the function for which they were designed, in spite of the difficulties outlined above. Currently, the Birmingham Northern Relief Road is awaiting construction and this will relieve some of the traffic pressure which gives daily flows of up to 150,000 vehicles per day.

|

Contract details

|

| Consultant: |

|

Sir Owen Williams and Partners |

| Contractor: |

C1: Dunston to Shareshill |

John Laing Construction Ltd. |

| |

C2: Shareshill to Darlaston |

The Sir Alfred McAlpine & Son Ltd – Leonard Fairclough Ltd Consortium. |

| |

C3: Darlaston to Bescott |

Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd |

| |

C5: Bescott to Rayhall triangle |

Taylor Woodrow Construction Ltd |

| |

C6: Rayhall to Great Barr |

R.M. Douglas Construction Ltd |

| |

C7: Great Barr to Perry Bar |

R.M. Douglas Construction Ltd |

| |

C8: Perry Bar to Bromford (Gravelly Hill Interchange) |

A Monk & Co Ltd |

| |

C8A: Advance River Works |

R.M. Douglas Construction Ltd. |

| |

C9: Bromford to Castle Bromwich |

Marples Ridgway Ltd |

| |

C10: Castle Bromwich to Maxstoke |

Sir Alfred McAlpine & Son Ltd |

| |

C11: Maxstoke to Ansty |

George Wimpey & Co Ltd – Kier Ltd Consortium |

| |

C12: Ansty to M1 at Catthorpe |

John Laing Construction Ltd. |

| |

Contract A |

Christiani-Shand |

| |

Contract B |

Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd |

| |

Contract C |

W.&C. French (Construction) Ltd. |

| Planning Period: |

|

1958-1969 |

| Construction Period: |

|

1964-1972 |