The M40 up to Oxford was planned with its extension in mind. In the late 1960's, the Ministry of Transport carried out a feasibility study on a new route between Oxford and Birmingham while it was considering the development of a strategic motorway network for the country.

The M40 up to Oxford was planned with its extension in mind. In the late 1960's, the Ministry of Transport carried out a feasibility study on a new route between Oxford and Birmingham while it was considering the development of a strategic motorway network for the country. It was to provide a direct link from the Midlands and North West to the South coast ports and an added route to London and the South East as an alternative to the M1. In 1972 it was added to the trunk road programme.

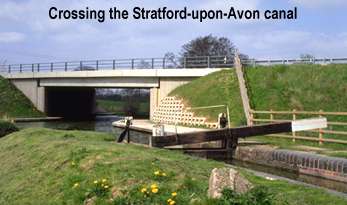

The public and representative groups were involved in route planning from the early stages. One of the stretches through which the motorway was likely to pass but which called for sensitive treatment was the section in the Cherwell Valley south of Banbury. Ministers decided to broaden the consultative process on this stretch and in May 1973 the public were invited to comment on three alternative routes. This was the first public consultation ever held on a road scheme and was a great success, generating considerable interest. Public consultation procedures are now a standard part of the development of major new road schemes.

The public Inquiry into the section of M40 between Warwick and the M42 and the linked M42 proposals around the south of Birmingham lasted from June 1973 to January 1974. The Secretary of State announced his decision on the line of the route in 1976. That decision was challenged in the High Court (which quashed the decision) the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords; the final judgement, in the Department's favour, was not reached until 1980. Even then, the decision was taken that this section would not be built until the Secretary of State had approved a bypass of Banbury.

The Department published a draft line for the full length from Warwick to Waterstock in 1981 and The Public Inquiry to consider objections to the line convened in Banbury in September 1982 and closed, after 117 sitting days in June 1983. After further legal processes the line from Warwick to Wendlebury was finally approved and was able to move forward into detailed design and the remaining statutory procedures. The final approvals for these and the statutory procedures for the section from Waterstock to Wendlebury were not fully received until March 1989.

Construction work started on the Warwick section in October 1987 on the first of the four contracts making up the Banbury section of the motorway in February 1988 and on the section from Waterstock to Wendlebury in July 1989. The Warwick section opened to traffic in December 1989 and the stretch from Waterstock to Warwick in January 1991.

The section of the A43 between its interchange with M40 at Wendlebury and its junction with the A34 at Pear Tree Hill was also upgraded. This ensured that there would be a high standard route between the Midlands and London from the day the motorway opened.

During the 1970's the responsibility for the M40 lay with the Department's Midland and Eastern Road Construction Units - their Warwickshire and Buckinghamshire Sub-Units respectively. After the Department reorganised its regional offices in 1980, Ove Arup & Partners were awarded the commission for the length between M42 and the North of Banbury and Sir William Halcrow & Partners the one for the Southern section to Waterstock.

Contract Details |

||||

Contract |

Contractor |

Length |

Tender Value |

Starting Date |

|

Warwick North (....J16) |

10.7km |

£26.6m |

Nov 1987 |

|

|

Warwick South (J13....) |

R M Douglas |

7.9km |

£22.4m |

Jul 1987 |

|

Gaydon (J12 to J13) |

R M Douglas |

11.4km |

£34.0m |

Jan 1989 |

|

Banbury IV (J11 to J12) |

15.8km |

£51.7m |

Aug 1988 |

|

|

Banbury III (J11 TO J12) |

Tarmac (now Carrilion Construction) |

12.2km |

£52.5m |

Feb 1988 |

|

Banbury II (J10 to J11) |

Mowlem Civil Engineering |

7.3km |

£18.0m |

Apr 1988 |

|

Banbury I (J9 to J10) |

Tarmac (now Carrilion Construction) |

8.5km |

£24.2m |

Dec 1988 |

|

Waterstock - Wendlebury (J8A to J9) |

McAlpine/Fairclough(AMEC) Joint Venture |

20.1 km |

£63.9m |

Jul 1989 |

|

[Length descriptions by junction are approximate only] |

Total: |

93.8km |

£293.3m |

|

The M40 sets new standards in the treatment of its environment. The Department has taken unprecedented steps to blend the motorway into its surroundings and to protect and encourage native plants and wildlife. This has involved detailed surveys and investigations by environment and landscape experts throughout the development of the scheme. In response to their recommendations, the Department has undertaken extensive landscaping works and planting to ensure that the disturbance to affected areas is minimised.

Building the M40 has offered a challenge to bot designers and contractors alike. Geologically it begins in the south on the Oxford Clays before climbing to the more open rolling limestone uplands lying east of the Cherwell River. The route then cuts through an escarpment to enter the Cherwell Valley crossing the valley twice as it skirts to the east of Banbury. Now in Lias Clays the route runs along the Warmington Valley between the limestone ridges of Edge Hill and the Burton Dassett Hills. From here it emerges out of the Warwickshire plain to cross the River Avon south of Warwick. Underlying a significant length of this route are deep but workable coal measures. Also there are flood plains where the road crosses the Avon and Cherwell Rivers.

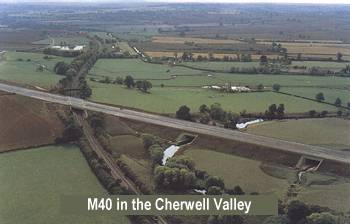

British Coal have stated that it is not their intention to mine the coal before the turn of the century but the Department decided that the road and bridges should be designed to allow for the possibility of subsidence. Forty eight bridges on the route were designed to do so. An example is the elegant Foxhill Bridge, designed by Sir William Halcrow and partners, which crosses the motorway as it plunges down into the Cherwell Valley. It is built of fabricated steel beams which allow the deck to be jacked up should the ground settle unevenly.

British Coal have stated that it is not their intention to mine the coal before the turn of the century but the Department decided that the road and bridges should be designed to allow for the possibility of subsidence. Forty eight bridges on the route were designed to do so. An example is the elegant Foxhill Bridge, designed by Sir William Halcrow and partners, which crosses the motorway as it plunges down into the Cherwell Valley. It is built of fabricated steel beams which allow the deck to be jacked up should the ground settle unevenly.

As with the bridges the pavement was designed to allow for possible future settlement. Over the mining area the main layer of the pavement is a 230mm slab of continually reinforced concrete roadbase (CRCR), which has a steel reinforcement at its mid-depth. Four different contractors laid CRCR on four different contracts; all used continuously-fed concrete trains which laid concrete across half the width of the carriageway. Rather than putting the reinforcement into place before they laid the concrete, both Douglas and Balfour Beatty poured half the depth of concrete and then placed pre-formed mats of steel reinforcement which they covered with the upper half of the slab.

Using this method on their concrete train Balfour Beatty set a British record of 1232 metres for the length of concrete laid in one shift.

On Banbury Bypass Contract 2 half the contract runs through various strata of limestone. Here Mowlem Civil Engineering, the contractors, used a Vermeer trenching machine to cut the drainage trenches. It is thought to be the only one of its kind in the country. It ensures that trenches can be cut much faster and more neatly than by breaking or blasting: it can cut a trench lm wide and 2.7m deep at a rate of between 40 to 100 metres per hour.

In order to carry the motorway across the flood meadows of the Cherwell near Kings Sutton, on Banbury Bypass Contract 3, Tarmac (now Carrilion Construction)used a ground improvement system known as vibropiling to strengthen the poor ground before building the embankment. Under this system jets of water force, a hole through the soft soil which are then filled with stones as the vibrator is extracted. The stone columns allow water to percolate through the motorway support, preventing water from building up unequally on one side of the road.

In order to build the road more quickly, Tarmac (now Carrilion Construction) negotiated with the owners of land by the motorway to establish a haul road along

the site. This enabled them to take men, equipment and materials to any point along the contract and to continue work on structures while earthworks were being carried out.

Avon Bridge

The widest river the motorway crosses is the Avon. Ove Arup and Partners designed a slender open-span bridge to cross the river 40 metres downstream from the existing one. This carries the A41 and was faced with stone when it was completed in 1967. R M Douglas built the new bridge to carry the motorway's northbound carriageway; 1,000 cubic metres of concrete were poured in one continuous operation lasting 15 hours to form the deck of this bridge. Traffic was then diverted onto this bridge whilst the A41 bridge was widened to become the southbound carriageway. Its Cotswold stone facing was removed, stored and re-used on the widened bridge.

Because of the change of route to avoid Otmoor the last contract to be awarded was from Waterstock to Wendlebury. It was expected that because it was the longest section and the most expensive it would take up to a year to complete after the other sections had been opened. This created a challenge to see by how much the time gap could be reduced. Everyone, including the Department of Transport's staff, the consulting engineer and the contractors responded to this challenge. They not only made up the time but had the scheme completed six months early and two months ahead of the opening date. The 20-kilometre contract was completed by the joint venture between Alfred McAlpine and Fairclough (AMEC) in only 16 months, a record which will be extremely hard to beat. A great deal of earth had to be moved to build the motorway and much of this was used to create embankments to provide protection and noise bunds. The contractors negotiated with nearby landowners to tip the remainder on their land. This was then contoured and covered with topsoil so that it could be returned to agricultural use.

A number of the contractors opened quarries near the site to supply themselves with the material which, along with excavated soil, was needed to fill the embankments. This avoided the need to carry large amounts of materials across country. The joint venture between Alfred McAlpine and Fairclough (AMEC) opened such a quarry near Merton. Once they have extracted all the limestone they need from the quarry it will be filled with water and made into a landscape feature.